|

These

divrei Torah were adapted from the hashkafa portion of Rabbi Yissocher

Frand’s Commuter Chavrusah Tapes on the weekly portion: #1234 Can Your

Wife Put Your Tefilin on You? Good Shabbos!

The Mishna

(Pesachim 35a) enumerates the types of grains that can be used for making

matzah to

fulfill the mitzva

of eating matzah

on Pesach. The Gemara notes that the five grains listed in the Mishna are

an exhaustive list, implying that—for example—rice or millet, which are

not mentioned in the Mishna, cannot be used to make matzah. What is

wrong with using rice or millet? The Gemara infers a connection between chometz and matzah from the pasuk “You shall not

eat upon it chometz,

seven days you shall eat upon it matzah,

the bread of poverty…” (Devorim 16:3): That which can potentially become chometz (leavened)

is the type of grain from which we can make matzah. Rice, millet, and other grains

that are not listed in the Mishna can reach the state of sirachon (spoilage)

but they cannot reach the state of chimutz

(leavened).

This concept may

seem counterintuitive. Since we are so particular about preventing matzah from becoming

chometz,

shouldn’t we go out of our way, when baking our matzah, to

specifically use grains which do

not leaven? Why do we put ourselves in a situation where,

if the dough is not baked quickly enough, it will become chometz? With all

the difficult stringencies that are involved in baking matzah, why didn’t

the Torah sanction the use of a type of grain that will never become chometz? Why does

the Torah insist that we use a type of grain which could become chometz,

necessitating the baker to zealously guard that it does not so become?

The Tolner Rebbe

from Yerushalayim gave several drashas

when he was in Los Angeles for Parsha Bo several years ago. In one of his

drashas,

he commented that in this particular halacha

lies a great practical lesson.

Chazal teach that chometz is symbolic

of the Yetzer haRah

(evil inclination). On the other hand, matzah

is symbolic of the Yetzer

haTov (good inclination). Chometz

rises. It is puffy. It is blown up. This is symbolic of a person’s

haughtiness and passions. Matzah,

which is plain and is flat, does not rise or get blown up. It is not

haughty. It represents modesty, humility and the ability to manage with

the bare necessities of life. In other words, chometz and matzah are at the opposite ends of the

spectrum. Chometz

represents negative spiritual character traits, and matzah represents

positive spiritual character traits.

The lesson,

therefore, is that the Torah wants us to take that very thing that could

potentially become chometz

and make it into matzah.

Extending the analogy of the Yetzer

haRah and Yetzer

haTov, the Torah wants us to take that which is our Yetzer haRah (our

problems, our temptations, and our foibles) and convert it to Yetzer haTov. This

means that man’s spiritual mission is to try to work on those very

personality traits and characteristics that in the past have proven to be

his weak points. If a person is mute then he will not receive reward in

the World to Come for not speaking lashon

haRah (gossip, slander, etc.). That is not his problem. The

reason that it is not his problem is because of an unfortunate physical

disability. But nevertheless, he will not receive reward for that because

there is no challenge.

Likewise, for

example, if a person is unfortunately blind, he has no challenge of “shmiras aynayim” (guarding

his eyes) from viewing inappropriate matters. That is not his challenge.

The avodas ha’adam

(man’s spiritual challenge) is to take those very things that are areas of

spiritual weakness, where perhaps in the past he has fallen short

of the Torah’s ideals, and to conquer them and elevate them. In fact,

perhaps he will even be able to take that very thing and turn it into a dvar mitzvah.

Let the person

channel his passions—which have perhaps led him astray in the past—in a

positive direction. This is the symbolism of the chometz and the matzah. Don’t try

making matzah

out of something that cannot become chometz

anyway. That is no great accomplishment! Take something that without

careful watching and care can

become chometz.

That is the very item we turn into a “cheftza

d’mitzvah” (an entity with which a positive command is

fulfilled).

This halacha regarding

the grains with which matzah

may be baked is a metaphor for a person’s spiritual mission. We must seek

out that which has been our Yetzer

haRah and turn it into our Yetzer

haTov.

We can perhaps

relate this idea to a very peculiar Medrash (Yalkut 187) that we have

mentioned in the past. A certain Tanna fasted 85 times because he did not

understand a particular matter: Dogs are creatures which are called azei nefesh (brazen,

insolent) in Yeshaya 56:11. And yet, in Perek Shira, in which each of the

animals recites Shira

(Song of Praise) to the Ribono

shel Olam, the dogs are recorded as saying “Come let us bow

down before Hashem our G-d.” This Tanna, Rav Yeshaya, the student of Rav

Chanina ben Dosa, was very perturbed by this. How could it be that these

dogs, which possess the attribute of insolence (azus), are the ones

that recite the praise “Come let us bow down before Hashem our G-d?”

Therefore, he fasted 85 times to beseech Divine Help in understanding

this anomaly.

The Medrash relates

that a malach

(heavenly angel) came down and revealed “the secret” to him. At the time

of Yetzias Mitzrayim (the Exodus), the pasuk

says, “But against the Children of Israel a dog will not sharpen its

tongue…” (Shemos 11:7). In the merit of this ‘action,’ the dogs merited

to recite the pasuk

attributed to them in Perek Shira.

The precise point

of this Medrash is the idea mentioned above: Dogs are full of chutzpah by nature.

It is a dog’s innate nature to bark, especially when it senses that

something unusual is transpiring. For the dogs not to bark at such a time

demonstrates a tremendous conquest over their normal inclinations. The Ribono shel Olam

appreciates that. Thus, the Medrash’s point is the following: Despite the

fact that dogs are azei

nefesh, and in spite of the fact that they normally bark,

they were greatly rewarded by virtue of the fact that they conquered this

natural inclination and remained silent at the time of the Makas Bechoros

(the Plague of the First Born). We learn from dogs to people: People too

should strive for kvishas

hayetzer (conquering their evil inclination) in service of Hashem.

The Lesson of Sensitivity in Halacha

On that same visit,

the Tolner Rebbe shared another practical lesson from a different halacha as well. The

halacha is

that the Korban Pesach

(Paschal Offering) needs to be eaten “b’chaburah”

(in groups). If two different chaburahs

are eating in proximity—even in the same room—no individual is allowed to

leave his chaburah

and go to the other chaburah.

They are certainly not allowed to leave the room and go to another room to

join a different chaburah.

The Mishna

(Pesachim 86a) states that if two groups are eating in one room, one

group sitting at one table and the other group sitting at another table,

they may not even face one another. Each group must face only the people

in their own group. The halacha

is that if in fact they do turn around and face the other group, they are

no longer allowed to eat the Korban

Pesach. That is considered “eating in two different groups,”

which is a Biblical prohibition.

The Mishna allows

only one exception to this rule: A bride may turn away and eat. The

Rambam in fact codifies this law (Hilchos Korban Pesach 9:3-4). The Gemara

explains the reason for this leniency (which is also mentioned by the

Rambam). It is because the kallah

(during the first thirty days after her marriage) is embarrassed. During

the first month after her marriage, she is particularly self-conscious

and she thinks people are staring at her.

Consider the

following: On the night of the Seder,

Leil Pesach,

everyone is on a different level. We all know the importance of the mitzvos.

Unfortunately, today we do not have the Korban Pesach, but we still have a

certain seriousness and focus regarding our matzah, marror and daled kosos. We focus on properly

fulfilling these mitzvos

of the evening. We can only imagine what an elevated state people were in

during the time of the Beis

HaMikdash when everyone had a Korban Pesach at their table as well.

Do we really think

that at such a moment people would be staring at a kallah to see how

she looks or how she eats? The answer is no! So why did the kallah think that?

It was a figment of her imagination. She is embarrassed because she

THINKS people are looking at her. Therefore, she is embarrassed. Nobody

is staring at her while they are eating the Korban Pesach!

Do we need to

accommodate this figment of her imagination and let her transgress that

which would otherwise be a Biblical prohibition? Apparently, yes!

Apparently, we acquiesce to her mishugaas

(foolishness). Why is that so? What is the lesson?

The lesson is

sensitivity. We need to account for a person’s sensitivity, even though

it may be based on a figment of their imagination. If we need to be so

careful and sensitive when there is really nothing there, how much more

so must we be careful and sensitive when people ARE justifiably sensitive

about certain things.

This is an amazing

insight. We let the kallah

do something that under normal circumstances should disqualify her from

eating the Korban

Pesach, simply because of her embarrassment regarding a

non-existent phenomenon.

The Tolner Rebbe

added that we see the same principle in another halacha that is more

familiar to us. There are five things prohibited on Yom Kippur, one of

which is that a person is not allowed to wash any part of his body. There

is a dispute among the early commentaries whether anything beyond the

prohibition to eat and drink is a Biblical prohibition, but there are

those who hold that all five ‘prohibitions’ are Biblical.

If that is the

case, why does the Mishna (Yoma 8:1) allow a kallah to wash her face on Yom Kippur?

The allowance is made “so that she does not look unseemly to her (new)

husband”. Again, do we think a kallah,

within thirty days of her chuppah

is going to become ‘unseemly to her husband’ because she does not wash

her face one day? Will this cause her husband to lose interest in her and

think she is not beautiful anymore? Of course not! How do we permit a

Biblical prohibition for such a reason?

It is the same

answer. Yes, it is a figment of her imagination, but that is the way she

thinks and that is the way she is super sensitive. Since in her mind, she

is afraid she might lose her husband’s adoration, we again make an

accommodation for that.

This again is a

tremendous lesson in sensitivity. How sensitive must we be to a person’s

feelings, even when those feelings are not based on reality. How much

more so is that the case when we know that people are hurting, for

example widows, orphans, or divorced people. These are classic examples

of people who are in pain. These are realities of life. People who are in

pain or sick or beaten down are very sensitive. If we need to be

sensitive to these two kallahs—by

the Korban Pesach

and on Yom Kippur—al

achas kamah v’kamah, we must be sensitive to people whose

embarrassment is based on fact and not just fiction.

Transcribed by

David Twersky; Jerusalem DavidATwersky@gmail.com

Technical

Assistance by Dovid Hoffman; Baltimore, MD dhoffman@torah.org

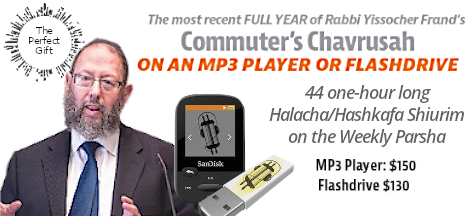

This week’s write-up

is adapted from the hashkafa portion of Rabbi Yissochar Frand’s Commuter

Chavrusah Series on the weekly Torah portion. A listing of the halachic

portions for Parshas Bo is provided below:

- # 040 Amirah L’Akum: The “Shabbos Goy”

- # 083 The Burning Issue of Smoking

- # 131 Sephardic vs. Ashkenazic

Pronunciation Is There a Correct Way?

- # 178 Tefillin and Long Hair

- # 224 Kiddush Levanah

- # 268 The Consequence of Dropping Tefillin

or a Sefer Torah

- # 314 Chumros in Halacha

- # 358 Mezzuzah-What Is a Door?

- # 402 Doing Work on Rosh Chodesh

- # 446 The Dog In Halach

- # 490 The Lefty and Tefilin

- # 534 Rashi & Rabbeinu Ta’am’s

Tefillin

- # 578 Tefilin on Chol Hamoed

- # 622 Ya’ale V’Yovo

- # 666 Dishwashers on Shabbos

- # 710 Checking Teffilin by Computer

- # 754 Cholent on Pesach – Why Not?

- # 798 Kiddush Lavanah – Moonshine on Purim

- # 842 What Should It Be? Hello or Shalom?

- # 886 Women and Kiddush Lavana

- # 930 Eating Matzo An Entire Pesach – A

Mitzvah?

- # 973 Yaaleh Ve’yavoh

- #1017 Kiddush Levana on a Cloudy Night

- #1061 Rosh Chodesh Bentching (Bircas

Ha’chodesh)

- #1104 How Long Must You Wear Your

Tefillin?

- #1147 Hashgacha Pratis – Divine Providence

– Does It Apply To Everyone?

- #1190 Kiddush Levana Issues

- #1234 Can Your Wife Put Your Tefilin on

You?

- #1278 Oy Vey! My Tephillin Have Been Pasul

Since My Bar Mitzvah

- #1322 Chodesh Issues: Women and Kiddush

Levana; Getting Married in Last Half of Chodesh?

- #1366 I Don’t Open Bottle Caps on Shabbos,

You Do. Can I Ask You to Open My Bottle?

- #1410 Saying U’Le’Chaporas Pesha In Musaf

Rosh Chodesh In a Leap Year

- #1454 Why Don’t We Wear Tephillin at

Mincha?

- #1498 What Should You Write January 21

2022 or 1-21-22 Or Neither?

A complete

catalogue can be ordered from the Yad Yechiel Institute, PO Box 511,

Owings Mills MD 21117-0511. Call (410) 358-0416 or e-mail tapes@yadyechiel.org or visit http://www.yadyechiel.org/ for

further information.

|

Comments

Post a Comment