Likkutei Sichot: Noach

Likkutei Sichot: Noach

Eternally Relevant Truths: After the Flood

As is customary at such gatherings,1 our starting point is the weekly Torah reading. For the Torah and its directives are eternal,2 applicable at all times and in all places.

The fact that we study a different portion every week indicates that each reading contains lessons applicable to the events which take place during that week.3

The conclusion of this week’s Torah reading relates that the people who lived shortly after the Flood built a city and a tower, “lest we be dispersed throughout the earth.”4 G‑d was displeased with their conduct, and thwarted their efforts.

On the surface, it is difficult to understand why the Torah relates this story. What can we learn from it? And yet, the fact that the Torah tells us this story and does so in detail, while mentioning many laws with only a brief allusion indicates that this episode contains a deep lesson for our ancestors, for ourselves, and for our descendants.

The story took place shortly after the Flood, from which only a small portion of mankind was saved. After the “flood” of the Holocaust, which destroyed millions of Jews, those who remain must derive a lesson from those who survived the first Flood, and avert the negative consequences which came about from their conduct.

Building a High Tower with Narrow Sights

Taking a quick look at the behavior of the dor haflagah (the generation which was dispersed), its sin is not readily apparent. Obviously, the building of a city and tower was against G‑d’s will, as reflected by His special efforts to abort the endeavor, but why the city and tower were undesirable is not explicitly stated.

The Torah tells us that the intent of the construction was to “make for ourselves a name.”5 The people feared that they would be dispersed throughout the world, and so they built a city in which they could live together. And they built a high tower so that:

a) even those in remote areas could see the city;

b) watchmen could be posted to see that no enemies would be able to enter the city.

On the surface, these activities are not sinful. What then was the problem?

The problem was that the people built with only one goal: that their reputation continue for all time.6 They had no higher motive. There is a fundamental difficulty in this: They were thinking only of themselves, without looking for a higher purpose in life.7 Moreover, when his own welfare becomes a person’s only purpose in life, he is not concerned with the justice or fairness of the means he employs.

The error inherent in such behavior is particularly severe after the Flood. For as Noach told the people of his generation,8 the Flood came about because of their undesirable conduct. Therefore, it would have been appropriate for the survivors to make the spiritual welfare of the generation their first priority, and to endeavor to live for a higher purpose.

But this was not on their minds at all. Instead, the intent of the survivors was to engrave their names in the annals of history. This was their sin, and for this reason, G‑d was displeased with their conduct.

The Need for Deeper Purpose

The lesson is obvious. When a person is saved from a catastrophe, he should endeavor to insure that the situation which brought about the “flood” does not recur. This should be done so that, as it is written:9 “the travail shall not arise a second time.” Building a city and tower with no other intent than that it be tall and formidable will not accomplish this purpose. For the construction to endure, it must serve a higher purpose. This will bring success to the building of any city, and transform all the forces hindering the city’s growth into helpful influences.

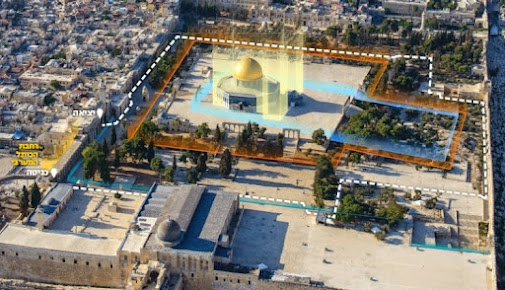

Building the City of Holiness

The concepts of “city” and “tower” have parallels in the realm of holiness.10 “The city of our G‑d,”11 is permeated by holiness. Such a city requires a tower, i.e., a synagogue and a house of study, as reflected in the law which requires a synagogue to be higher than all other buildings in the city.12

To clarify the intent: In every city there should be synagogues, houses of study, and yeshivos. It is necessary to devote our skills and energies to making these structures greater and more substantial, that they should be the towers concerning which it is stated:13 “The name of G‑d is a tower of strength; the righteous run into it, and are saved.” This is a tower which offers true protection, not only from those enemies who are visible, but also from those who conceal their designs.14

Setting priorities in this way brings twofold benefits: Because one is carrying out G‑d’s will, there will be great success in building the city and tower of holiness. In addition, one receives the reward implied by the phrase “Let us make for ourselves a name,” for the names of the people active in these endeavors will be immortalized in the annals of Yiddishkeit and Torah, and in the records of righteousness and justice. All those who help build the eternal city and tower of faith will receive a measure of this eternity.

Twofold Blessings

We have to build yeshivos in which children are trained to study Torah, and from which Torah can be spread throughout the world. The yeshivos are the tower of a city; they must be made larger and more substantial so that they can open new divisions and accept more students. And as mentioned previously, lending a shoulder to the task of building the towers of holiness will bring twofold blessings: the benefits of fulfilling G‑d’s will, and the dividends this brings in one’s personal affairs. And most of all, one’s activities will be granted an eternal dimension through involvement in Yiddishkeit.

May G‑d grant you success in building the yeshivos, increasing their capacity manyfold. And thus, at our next gathering we will not think merely of covering the deficit, but rather of raising the towers of Torah even higher. May G‑d grant you success in this task, and also in your personal affairs.

(Adapted from the sichah delivered to the supporters of

the Lubavitcher Yeshivah, Tomchei Temimim, Cheshvan 4, 5720)

Two Generations, Two Types of Punishment

With regard to the generations between Noach and Avraham mentioned at the conclusion of this week’s Torah reading, the Mishnah states:15

There were ten generations from Noach to Avraham to indicate how great is His patience, for all those generations repeatedly angered Him, until Avraham our father came and received the reward of them all.

This statement provokes questions: What reward did Avraham receive because of the ten preceding generations? If they “repeatedly angered Him,” what reward was there for Avraham to receive?

Also, previously, the mishnah stated:

There were ten generations from Adam to Noach to indicate… until He brought upon them the waters of the Flood.

In this earlier statement, the mishnah does not mention that Noach received a reward generated by the conduct of the previous generations. The rationale is easily understandable. Since these people “repeatedly angered” G‑d, they did not produce any reward.

This makes the later statement even more difficult to understand. Since these generations also aroused G‑d’s wrath, why did Avraham receive a reward for their activities?

This difficulty can be resolved by comparing the two sets of generations. The generation destroyed by the Flood (dor hamabul) was the last of the generations between Adam and Noach. It included all the previous generations, as reflected by the fact that the Flood was able to wash away the sins of the previous nine generations. The generation dispersed throughout the earth (dor haflagah) was the last of the ten generations between Noach and Avraham, and its conduct also encompassed that of the previous generations.

We find paradoxical elements regarding the sins of the dor hamabul and the dor haflagah. With regard to the punishment received in this world, the dor hamabul was chastised far more severely.16 It was totally annihilated; indeed, “[the flood] obliterated every being on the face of the earth.”17 In contrast, the dor haflagah was merely dispersed.

With regard to punishment in the World to Come, however, we find the reverse. All authorities agree that the dor haflagah will not be granted a portion in the World to Come,18 while with regard to the dor hamabul, there is a difference of opinion. Although the Mishnah19 and one opinion in the Zohar20 state that it will not be granted a portion in the World to Come, other opinions maintain that it will. It is hard to understand why there is a difference in the punishments these people received in this world and those they will receive in the World to Come.

Between Man and Man and Between Man and G‑d

One of the fundamental principles of the Torah’s rules of causality is that punishment is meted out according to the nature of the blemish created by one’s conduct.21 The difference between the sins of dor hamabul and the sins of dor haflagah are explained by our Sages, and the difference in the punishment meted out varies accordingly.

The dor haflagah sinned against G‑d Himself, and desired to do battle with Him.22 Nevertheless, it was not wiped off the face of the earth. Why? Because in worldly matters between themselves the members of that generation conducted themselves with love and a comradely spirit: “they shared one language, and mutual concerns.”23

The dor hamabul, by contrast, did not sin against G‑d Himself. Its members were, however, thieves, and their lives were constantly plagued by strife and contention. And for this reason, they were wiped off the face of the earth.

On this basis, we can understand why the punishment received by the dor hamabul in this world is greater than that received by the dor haflagah. The sins of the dor hamabul involved interpersonal relations theft, robbery, and the like which disturb the order with which G‑d has structured the world. Therefore the primary dimension of the punishment that generation received was within this world. The sins of the dor haflagah, by contrast, centered on the relationship between man and G‑d. Therefore the punishment it received in the spiritual worlds was more severe than that of the dor hamabul.

It is true that a sin affecting the relationship between man and G‑d also has an effect in this world. For as Rashi clarifies in his commentary on the word Bereishis,24 the world was created “for the sake of the Torah, which is called reishis. ” And thus if we walk in His statutes,25 displaying the conduct ordained by G‑d, we will also receive reward in this world, for “I will provide you with rain in its season,”26 and the converse is also true.

And sins committed against one’s fellow man also have an effect in the World to Come, i.e., with regard to spiritual matters. For they also involve transgression of the Torah’s commandments. Nevertheless, interpersonal relations have a more obvious connection to this world, while relations between man and G‑d relate primarily to the World to Come.27

The Need to Appease One’s Colleague

There is another reason why the punishment meted out to the dor hamabul involved matters of this world. With regard to sins between one man and another, such as stealing, our Sages state that repentance, and even the purifying influence of Yom Kippur, are of no avail unless one appeases one’s colleague.28 If the person wronged does not grant forgiveness, the sinner’s repentance will not be accepted. Although the sinner does everything he can and thus his repentance is complete with regard to spiritual matters since the transgression involved matters of this world, his repentance is not sufficient until he returns the stolen object. For this purpose, he must follow the person he wronged even to a distant land to appease him.29

With regard to the spiritual consequences his conduct brings, by contrast, a sinner need only do what is necessary to appease his colleague; even if he was not able to find the colleague, or if the latter refuses to forgive him, his repentance is accepted.

The above applies, however, only with regard to the spiritual consequences; with regard to matters of this world which is the essential dimension of sins against one’s colleague since he did not correct the disruption which he caused, his repentance is of no avail.30

Accordingly, there is one opinion that the dor hamabul will receive a portion in the World to Come, for according to that opinion, they did repent. Nevertheless, since its members did not adequately appease each other, they still received punishment in this world.

Collecting Positive Influence

On this basis, we can appreciate why Avraham received the reward from the preceding ten generations although they “repeatedly angered G‑d.” The preceding generations deserved reward for the comradely deeds they performed. They themselves, however, were not worthy of receiving this reward, even in this world, because of their rebellion against G‑d. The positive forces which they drew down through their love and care for each other were turned over to the realm of evil. To cite a parallel, the Alter Rebbe rules31 that before a wicked person repents, the Torah which he studies and the mitzvos which he performs amplify the forces of evil. Because of his character, the positive energy which he generates is given expression in the realm of evil, rather than in the realm of holiness.

For this reason, Avraham “received the reward of them all.” Avraham’s service centered on deeds of kindness, and it was through such deeds that he drew people close to G‑d. Moreover, he even extended himself and prayed for the people of Sodom. Through these endeavors, he refined the generations which preceded him, and therefore received the reward which they generated.

To cite a parallel from the abovementioned ruling of the Alter Rebbe: When a sinner repents, he rescues the influence of the Torah and mitzvos which he performs from the forces of evil and, together with the person himself, these positive influences return to the realm of holiness.

These concepts do not apply with regard to the ten generations from Adam to Noach. The Mishnah does not state that Noach received the reward for their conduct, for two reasons:

a) they were not worthy of receiving a reward;

b) even if they had been worthy of a reward, Noach would not have received it, because he did not involve himself with the people of his generation, nor did he pray on their behalf. For this reason, the waters of the Flood are referred to as “the waters of Noach.”32

There is a lesson here. We are living in ikvesa diMeshicha, the last generation before the Redemption, when Mashiach’s approaching footsteps can be heard. The Divine service of all the previous generations has prepared the world for the coming of Mashiach, when the ultimate purpose of Creation will be consummated.33 And all the positive influence of the previous generations depends on the Divine service of the present generation.

By cleaving to the attribute of kindness (that quality of Avraham our Patriarch which draws Jews together through ahavas Yisrael) and awakening even those far removed to their Jewish heritage, we reveal the sparks of G‑dliness which are at the core of every Jew a treasure inherited from our grandparents and great-grandparents. By acting to bring these sparks of G‑dliness to their ultimate purpose the true and complete Redemption to be led by Mashiach one receives the reward for all the positive activity of those earlier generations.

(Adapted from the Sichos of Shabbos Parshas Bechukosai, 5722)

The sichah to follow was adapted from an address delivered at the annual meeting of the supporters of the Lubavitcher Yeshivah, Tomchei Temimim.

See Tanya, ch. 17, Kuntres Acharon, Epistle 5.

In this vein, see the statements of the Sheloh (Chelek Torah SheBaal Peh, Parshas Vayeishev): “The festivals of the entire year… relate to the weekly Torah readings in which they are celebrated, for ‘everything was designed by G‑d’s wisdom.’”

Bereishis 11:4.

Ibid.

See Zohar, Vol. I, p. 25b; Torah Or, the conclusion of Parshas Noach; Toras Chayim, the maamar entitled Vayehi Kol HaEretz.

See Guide to the Perplexed, Vol. III, ch. 13; Avodas HaKodesh, sec. HaTachlis; Pardes, sec. 24, ch. 10; Ikkarim, sec. 3, ch. 1; Mishnah, the conclusion of the tractate Kiddushin. Likkutei Torah, Parshas Re’eh, at the conclusion of the second maamar entitled Samti Kadkod (28d); Kuntres Beis Nissan, 5708 (Sefer HaMaamarim 5708, p. 136); Sichas Leil Simchas Torah, 5723.

See Sanhedrin 108a.

Nachum 1:9; Likkutei Sichos, Vol. XXIII, p. 306 note 55.

See Likkutei Torah L’Gimmel Parshiyos, the conclusion of Parshas Noach and the maamar Vihayeh Hanishar B’Tziyon (Sefer HaMaamarim-Kuntreisim, Vol. I, p. 278).

Cf. Tehillim 48:2.

Shabbos 11a, Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chayim 150:2).

Mishlei 18:10; see Likkutei Torah L’Gimmel Parshiyos, the conclusion of Parshas Noach.

See the maamar entitled Om Ani Chomah (Sefer HaMamaarim-Kuntreisim, Vol. I, p. 422).

Avos 5:2.

See Bereishis Rabbah 38:6, the commentary of Rashi to Bereishis 11:9. Note also Toras Chayim, Noach, p. 64a ff.

Bereishis 7:22.

Sanhedrin 107b, as accepted universally, without dispute.

Ibid.

Vol. I, p. 69a. See also Toras Chayim 78d.

Tanya, ch. 24.

Rashi, Bereishis 11:9; Sanhedrin 109a; Bereishis Rabbah 38:6.

Bereishis 11:1.

See also Osios d’Rabbi Akiva; Seder Rabbah d’Bereishis, sec. 5; commentary on Rashi and Ramban to Bereishis 1:1; Bereishis Rabbah, sec. 1; Vayikra Rabbah, sec. 36.

Vayikra 26:3.

Vayikra 26:4.

See the Rambam’s Commentary to the Mishnah, Peah 1:1.

Yoma 85b, Shulchan Aruch HaRav 606:1.

Bava Kama 103a, 104a; Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Mishpat, sec. 367 and commentaries.

See Yevamos 22b; Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Mishpat, loc. cit.

Hilchos Talmud Torah 4:3; Tanya, ch. 39; Torah Or, Parshas Chayah Sarah, maamar Lehavin… Sha’ah Achas (16b).

Cf. Yeshayahu 54:9. See Likkutei Sichos, Vol. I, Parshas Noach. I.e., he is held responsible to a certain degree for the Flood.

See Tanya, ch. 36.

Comments

Post a Comment